The new version of Workamper.com is...

Read moreGoing from Retirement into Ruins at Casa Grande

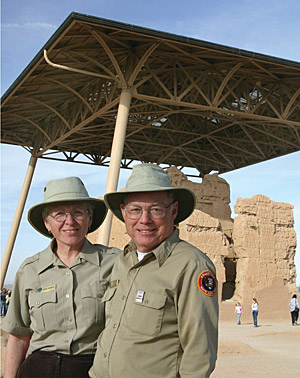

Going from Retirement into Ruins at Casa Grande

Some folks tell a rags-to-riches story. John and Grace Schafer from Ames, Iowa, plotted their course from retirement to ruins. On their first visit to Casa Grande Ruins National Monument at Coolidge, Arizona, the ancient culture of the Hohokam people—who lived and developed a sophisticated culture in the desert from approximately 300 BC until 1450 AD—intrigued the retired Iowa educators. Perhaps “intrigued” is inadequate for the passion they quickly developed for the people whose name simply means “those who have vanished.”

Some folks tell a rags-to-riches story. John and Grace Schafer from Ames, Iowa, plotted their course from retirement to ruins. On their first visit to Casa Grande Ruins National Monument at Coolidge, Arizona, the ancient culture of the Hohokam people—who lived and developed a sophisticated culture in the desert from approximately 300 BC until 1450 AD—intrigued the retired Iowa educators. Perhaps “intrigued” is inadequate for the passion they quickly developed for the people whose name simply means “those who have vanished.”

Taking up the RV lifestyle following John’s retirement as an instructor in the agriculture department at the Iowa State University, the Schafers spent the first couple of years touring the United States. Retaining a home in Ames, John says his goal in the RVing lifestyle is to spend no more than 50 percent of their nights in their Iowa hometown. Since their children, all educators who have more free time in the summers, beckon them to spend that season at home, volunteering at the Casa Grande Ruins during the wintertime fits perfectly into the Schafers’ traveling schedule.

“Immersing ourselves in the culture and history of this magnificent site gives us something productive to do,” Grace says. In 2006, the Schafers served their second season at Casa Grande Ruins, working as National Park Service interpreters three days a week. They lived with four other RVing couples in a campground set aside for volunteers.

“At this particular park, we set our own schedule,” Grace continues, noting that they worked a couple of autumn months before they traveled to Iowa for Christmas with their family. “We returned in January and worked until Easter.”

Upon their acceptance as volunteers, the Casa Grande staff asked the Schafers to read and read, and then build their own presentations for guided tours of the ruins, more literally translated as the Great House. Grace says that each volunteer interpreter researches and selects his or her focus for a 90-minute presentation. While John emphasizes the agriculture aspect of the ancient Hohokams, Grace found her heart connecting with the people and their daily lives in the harsh desert.

She initially empathized with the wife of the site’s first caretaker, Frank Pinkley. As a new bride, Edna Pinkley lived in a frame-sided tent pitched in the shadow of the Great House. She drew water from a hand dug well. As Grace wondered about Edna’s sparse existence in an unforgiving landscape, her thoughts shifted to the earlier inhabitants—the Hohokams.

On her first orientation tour as a volunteer, Grace remembers a cold January day. “I wore two jackets and still shivered,” she recalls. “I kept wondering how those people created a productive life in an environment that dropped to freezing some winter mornings and rose to a scorching 110 degrees in the summertime.

“Inside the Great House, our guide pointed to the walls patiently built into four-foot thick base by patting into small areas caliche, a lime-rich mud the people found several feet below the sandy desert floor. The workers allowed each two-foot square section to dry before adding more of the substance, thus creating strength in the walls that tapered to the roofline,” she continues. “I matched my hands to their fingerprints and the indentions of their palms in the walls. Suddenly, how they existed in the extremes of weather did not matter. At that moment, I connected to the people—their hearts and souls.”

A former elementary educator, Grace reinvented her career more than once. She moved into guidance and marriage counseling, and worked ten years at a community mental health center. However, her keen interest in history energizes her presentation with a mix of facts, lore, and legend about the desert farmers who were masters of irrigation. With mere sticks and stones, they dug a sophisticated 1,000 miles of canals in the Phoenix basin to carry water for their primary crops of corn, beans, and squash, and secondary cultivation of barley and cotton. Their system consisted of a network of diversion dams, ditches, and levees, indicating that the Hohokams understood the principal of gravity.

Casa Grande, once four stories high and 60 feet long, is the largest structure known to exist in Hohokam times. The skills of its builders had allowed the structure to withstand the ravages of time. The walls lean in and give strength to the eleven-room house. Archeologists project that hundreds of juniper, pine, and fir trees were carried or floated 60 miles down the Gila River to form ceiling or floor supports for the upper stories. Saguaro ribs were laid perpendicular across the beams of trees, then covered with reeds, and topped with a layer of caliche mud.

Casa Grande, once four stories high and 60 feet long, is the largest structure known to exist in Hohokam times. The skills of its builders had allowed the structure to withstand the ravages of time. The walls lean in and give strength to the eleven-room house. Archeologists project that hundreds of juniper, pine, and fir trees were carried or floated 60 miles down the Gila River to form ceiling or floor supports for the upper stories. Saguaro ribs were laid perpendicular across the beams of trees, then covered with reeds, and topped with a layer of caliche mud.

As amazing as the ancient ones’ building skills, the walls of the Great House face the four cardinal points of the compass. A circular hole in the upper west wall aligns with the setting sun during the summer solstice. Other openings align with the sun and moon at specific times, indicating that the Hohokam used the changing positions of celestial objects for their times to plant and harvest.

Who lived in the Great House? What mysteries guided them to mark the movement of the heavens through the holes in the walls? No one knows for certain. A government agent, Cosmos Mindeleff noted in 1890 that the structure could have been built to detect approaching enemies across the Gila Valley, or for observation of the Hohokam’s canal systems. He also speculates that the Great House had a clear view of the heavens.

Some archeologists believe the structure may have been a giant silo for the storage of the tribe’s crops. Or it may have been the residence of a high priest who viewed the rising sun through aligned portals and predicted astronomical events to the people. Remains of pit houses, central plazas, and compound walls, as well as solid, flat-topped structures called platform mounds, indicate that the Great House centered an important village.

Grace notes that the ancient Hohokams did more than survive in their harsh desert home. They thrived, taking time to create beautiful artwork in etched shells, pottery, and textiles. The remains of a ball court on the Casa Grande Ruins site is evidence that the people played. Discoveries of bones of rare birds, copper bells, and unusual shells indicate a trading society, possibly ranging as far south as the Gulf of Mexico. At one time, 100,000 Hohokam lived in the Phoenix Basin, and possibly over 1,000 lived in the village surrounding the Great House.

Casa Grande became the first cultural, historic site set aside in the United States. Since 1903, a roof has protected the prehistoric house. The current roof has covered the ruins since 1932.

Why did the thriving society of the ancient Hohokams decline? Where did they go? The walls of the old house hold these secrets, leaving only the handprints of its builders and inhabitants, and the speculations of those who visit the site.

“We scurry from destination to destination, seeking the beauty in our nation,” Grace says. “Often, we fail to make connections with these historic places.

“When we first came to Casa Grande Ruins, I asked myself, ‘What am I gong to do to help preserve this place?’” she continues. “John and I knew we had to commit to volunteer for two or three seasons to learn the Southwestern culture.” Will John and Grace continue to winter at Casa Grande Ruins? John answers, “While we believe this National Monument, serviced by the National Park Service, is a number one place to volunteer, we want to go other places and learn about other histories and cultures.”

Will the Schafers continue to volunteer? They both answer a resounding “Yes!”